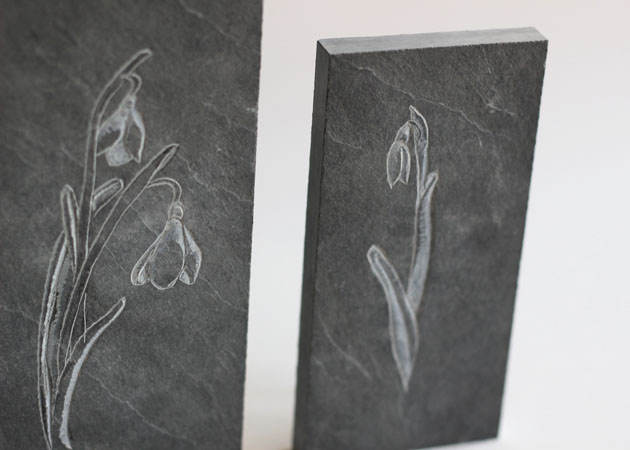

Snowdrops carved in stone

I’m working on Snowdrops, carving them into riven slate – I’m excited that my chisel leaves pale marks, helping to give the impression of white flowers.

It seems a marvel that they manage to push their delicate heads above ground in snow, frost, and flood, but they’re especially well adapted to life in the cold. Their leaves have hardened tips to help them break through frozen soil and their sap contains a form of antifreeze to prevent ice crystals from forming.

(Even though I have hardened tips on my chisels, it is still a tricky thing to get these fine flowers and dainty buds to emerge from the stone!).

As they’re amongst the first flowering plants in winter they’re associated with marking the ancient festival celebrating the middle of winter, halfway between the shortest day and the spring equinox.

After flowering, the snowdrop stems flop down and the seed pods develop on the surface of the soil. Each seed has a small oil and protein-rich appendage, and when the pods open these attract ants, which take them down into their nests as food for developing larvae. The seeds themselves remain untouched and, thanks to the ants are both dispersed to new locations and planted underground.

Most snowdrops found in the wild in Britain spread from the vegetative division of the bulbs, rather than by seed because they originally come from a cultivated sterile clone that is unable to set seed. Even when fertile species are around seed production is poor because there are few pollinating insects around in January and February to fertilise the flowers.

The snowdrop’s name Galanthus nivalis literally translates as ‘milk flower of the snow’.

Thankyou to Trevor Dines of Plantlife for some of the fascinating facts about snowdrops contained in this post.