Smoke Signals

It is a familiar sight at this time of year, billowing smoke on the horizon. I remember as a child playing camp and sending smoke signals back to the house with and old blanket waved over a makeshift wood fire. I hoped the smoke would be seen from far away, and my magic messages understood by whoever might pick them up. I kept a lookout for return signals.

This is a view of Lastingham taken from the top of Lidsty Hill, which leads out of the village, giving a good view out over Spaunton Moor. They’re busy here heather burning. Sometimes, if the wind blows this way, you can smell the scorching before seeing the smoke.

It worries me – at a time when all the birds seem eager and interested in nest-making and there are stirrings of Spring – it seems such a savage thing to be doing. I think about all the insects that live in the heather, those sheltering and those that burrow beneath its roots in the peaty soil.

Of course the burn is highly organised, sections are done in rotation – giving a patchwork effect over the moor. A mosaic of different aged heather. There is a ‘burning season’ – between sunrise and sunset from 1st October to 15th April. This controlled burning apparently keeps the heather young and vigorous – if left it eventually grows long and lank reducing its nutritional value. It is all about managing the conditions for sheep and grouse on this moor.

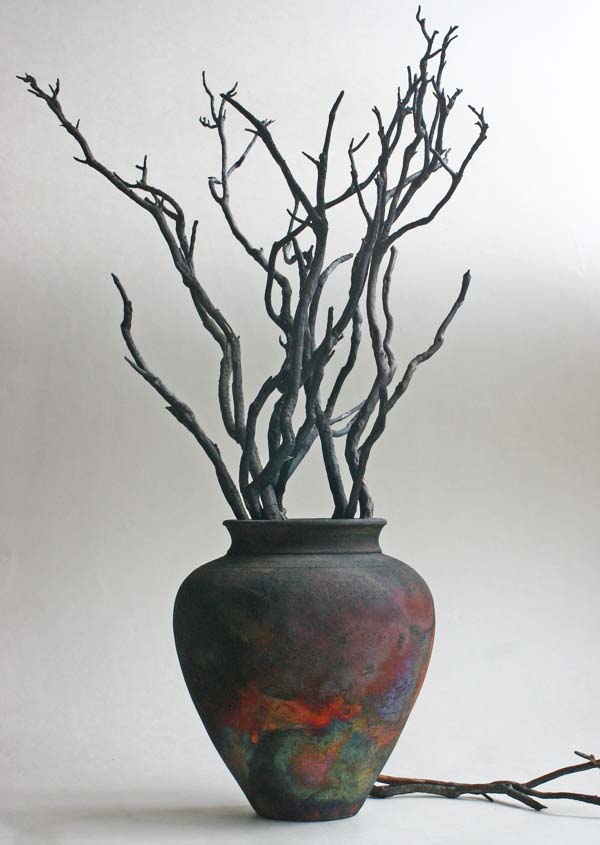

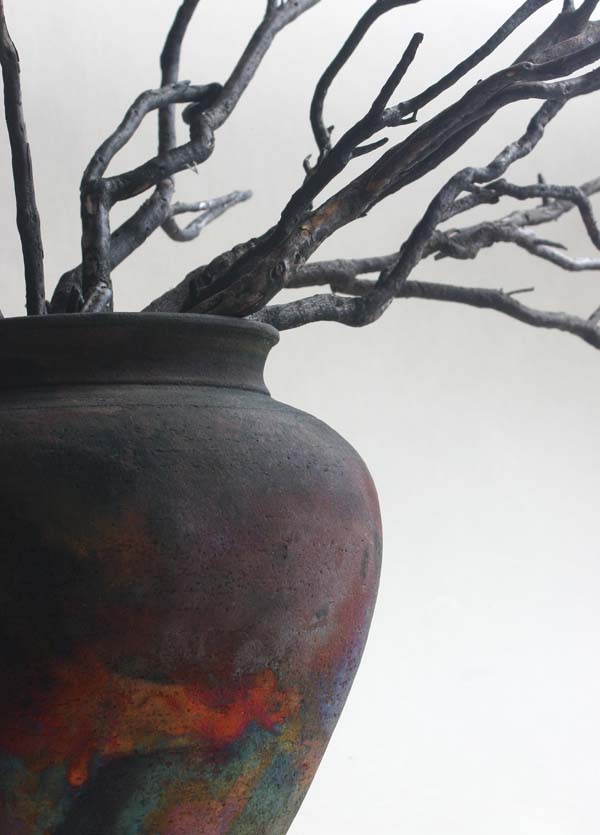

It leaves initially a brutal black landscape, unearthly, pungent.

I brought one or two twisty charcoal stems home.

I remember reading a few years ago about an artist who drew with the charcoal made from the burned heather stems, images of the horror of an uncontrolled fire on the North York Moors nearer the coast. This was in the height of the hot weather, everything was dry and a spark set the moor alight.

Heather is tough stuff – these controlled and scheduled burns are not supposed to go deep or long enough to affect the root systems of the plant and seem to ‘shock’ the seeds lying in ground into germinating quickly.

I found pieces of weathered stem, perhaps from a previous year’s burn. One piece is twisted and contorted, you can see the hardy fibres telling the persistence of its growth in the harsh moorland conditions. Immediately I’m seeing shapes and making images out of the swirls, just as I did with the smoke plumes I sent from my camp fire.

7 Comments

I’m in two minds about controlled burning. They do it here in the New Forest too. We looked at it a bit during a lecture and I understand that it helps keep the heather healthy. My worry is the same as yours- all the life out there that gets incinerated. I’m not a huge fan of shooting so I feel a bit aggrieved that so much of moorland management revolved around the game industry.

It seems a subject surrounded by much heated debate, and I am at a loss to understand the attraction of killing wild animals with lead pellets. So many of the landscapes which I have thought of as ‘natural’ turn out to be intensely ‘managed’. There is also private moorland acreage here which is given over to conservation, rather than run for grouse shooting, and this too is very controlled, for a different purpose, nature and conservation, but nevertheless being ruled by a strong hand of ‘unnatural’ intervention. It is a difficult balance. I’m trying to understand how we can best conserve.

From my house we are quite high up and can see over to Ilkley moor were they burn the heather, I have often wondered what the consequentness this practice has on the wildlife. There are other large moors that join onto Ilkley moor and grouse shooting dose take place in these areas. I once met the game keeper who was looking after the young grouse , making sure they were well , we had a good chat he was knowledgeable on all the birds on the moor, as well as the wild flowers, grasses, butterflies, moths and other wildlife on the moor.His balance between rearing the grouse (to be shot) and looking after the whole area seemed justified to me, (not everybody’s view) I have been up there when it’s been very hot, if the heather had been left to grow wild, I feel there would be a bigger risk of it catching fire and this would be devastating throughout the summer months. This kind of practice still needs to be understood and like you said “it’s a difficult balance”

Amanda xx

Amanda, thanks for your comment – I must look at the fire risks associated with new/old heather. The keepers here are hugely knowledgeable too – they should be, they’re out there all the time, seeing everything. They’re paid to know a lot, to ensure grouse safety and well-being, and provided the wildlife does not interfere with that, all’s well. The very act of burning and thus creating a certain age and growth pattern for heather is restricting habitat, giving favourable conditions for specific species. I found it interesting, from BTO records, that the primary breeding habitat for Curlew is moorland, and that laying begins mid April, through to the end of May. This suggests their need to find a partner, and establish a nest site, and breed are all happening at the same time as heather burning. Of course moors are big places, but it is this sort of potential disruption that worries me.

Hi Jennifer, thank you for your reply, I think due to my lack of knowledge on this subject, I have not looked at the bigger problems burning the heather has done. I was impressed by the gamekeeper and felt this particular man did care about the whole area even if the end result was sadly the demise of the grouse.

I have had a look on line and read a report from University of Leeds, which was published to day, the first day of the moorland burning season, which will run until 15 April 2015. Much to late in the season for birds…

The EMBER (Effects of Moorland Burning on the Ecohydrology of River basins)

,http://www.leeds.ac.uk/news/article/3597/grouse_moor_burning_causes_widespread_environmental_changes

Reading through the notes it looks like it is just coming to light the damage the burning has done, and in some areas the damage to nest sites and invertebrates would take many years to put right.

We were out in the country side to day and I commented on the fact I had not seen a Curlew this year. There is a lot of work to be done in this area, I just hope the Curlew dose not disappear before things change.

Amanda xx

Thanks so much Amanda for the link – this is another aspect – I’m looking forward to reading. There’s a study by the University of York, over five years comparing burning with cutting and getting scientific information about the processes. All good stuff! I’m away to digest the Leeds news you’ve linked to.

Very interesting isn’t it – in the York survey they are noting, similarly, that the myriad of mosses are also being destroyed by fire, that create the blanket bog vegetation – http://www.york.ac.uk/news-and-events/features/blanket-bog/